What You Need to Know:

• The English Poor Law system actually goes back to medieval times. However, the impact of the 1834 Act was that it transferred responsibility for the administration of poor relief from the parish to the newly-formed Poor Law Unions.

• Oddly enough, the poorest members of English society (who were the beneficiaries of the Poor Law system) often have the best ancestral records. That is because payments to impoverished individuals had to be carefully documented to prevent fraud.

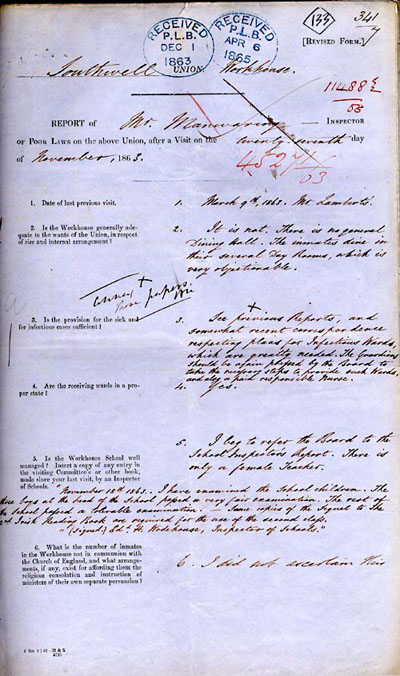

• There are various kinds of Poor Law records that are of interest to genealogists. Many of the letters, reports and memos mention specific individuals. For example, a Settlement Certificate was granted to a poor individual to prove that they had the right to legal settlement in a particular parish.

• Another type of Poor Law record is a Rate Book, which can be used to track when a family arrived and left a parish by recording the payments made to the family.

• Poor Law records are the best source for trying to track down the father of illegitimate children. The mother may have applied under the Poor Law system for financial relief or a Bastardy Record may have been created.

• Many of the Poor Law Union records have been indexed on the National Archive’s website. Access is free. [Historic Poor Law Union Records]

What You Need to Know:

• The largest impact to the revision of the marriage act affected nonconformists. Nonconformists could now marry in their own chapel provided a government appointed registrar was present. Previously, a Roman Catholic for example, would have to marry in an Anglican Church (for reasons of being able to claim the right to an inheritance) and then have a second form of marriage with a Catholic priest. After 1836, this two-step process was no longer necessary. Therefore, if your ancestors were not Anglican, you are less likely to find mention of them in Anglican parish records after 1836.

• Marriage licenses also became easier to obtain after 1836. Couples no longer had to go through the process of marriage banns, which involved a three week period of announcing a pending marriage in church. There were three groups of individuals who tended to favour marriage licenses over banns: pregnant brides (who did not want to wait the three weeks required by banns before getting married); people from outside the region (who could use a marriage license to forego the usual qualification of local residence required by banns) and the wealthy (who for some reason considered a marriage license as a means of displaying their social status).